Yellow Fever in New Orleans

Foul Odors and Yellow Fever in New Orleans

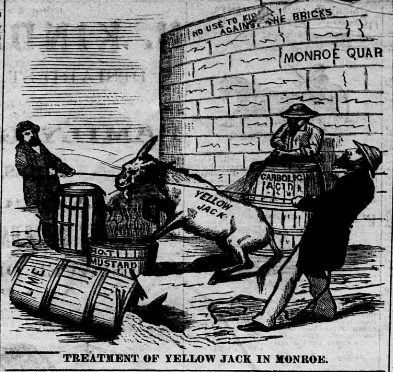

This Halloween season, let us all be grateful that we are not living in New Orleans in August of 1853. In this ill fated year the most deadly yellow fever epidemic in American History ravaged the crescent city. It is said that 1 in 15 people died from Yellow Jack that summer. No New Orleanian was untouched by the epidemic, though the populations that suffered most were immigrants, children, laborers and the poor. Those with means would either leave the city to avoid the epidemic altogether, or remain locked away in the cleanliness of their homes. But even those with access to health care and the most sanitary conditions were not spared the constant threat of death. The city was quiet that August—save the screams of the dying and the occasional cannon blast, shot in an effort to cleanse the bad air from the atmosphere—and reeked of death.

To protect against the "miasma" a plague doctor is pictured here wearing a beaked mask containing aromatic substances.

Prior to 1880 and the discovery of germ theory, no one knew how yellow fever was contracted. So in order to understand the depth of paranoia and distress that gripped the city, we must look at the belief that ruled the day: Miasma theory. Miasma is an ancient greek word that means pollution, and people who feared the miasma dreaded the effects of the bad air or noxious vapor that emanated from rotting organic matter—particularly the bodies of the deceased. It is then no wonder why in 1789 the burial ground in colonial New Orleans was relocated from St. Peter and Burgundy streets, within the city limits, to its current position on St. Louis and Basin streets, which was outside the city at the time. This dreaded smell had a mind all its own, and could crawl up your nose, infect your brain, and render you its next victim.

If you did so happen to contract the disease, your descent into illness came quickly and dramatically. Your skin would turn yellow with jaundice, making you incredibly sensitive to the light of day. Your body would start to shrivel up, making you appear gaunt, and in the case of your shrinking gums, make your teeth appear longer than usual. Finally, and this was often the death knell for victims of the disease, you would cough up blood as a result of your body eating itself from the inside out. When you put the pieces together, it is no wonder than belief in vampires and the undead was so common in colonial New Orleans, and remains to this day.

A representation by Robert Seymour of the cholera epidemic of the 19th century depicts the spread of the disease in the form of poisonous air.

The last major epidemic of yellow fever to strike New Orleans hit in 1905. Shortly after, scientists discovered the truth behind this heinous disease, and found that it had been a bite from a blood sucker all along! But instead of the sanguinarian vampires of our nightmares, the real villain were the most insidious and preponderant of vampires…the mosquito of course! Mosquitoes love filth and swampy climate making New Orleans the perfect breeding ground for these disease carrying insects. At the turn of the 20th century, the city began installing pumps to deal with the standing water, and the disease became more manageable as the mosquito population came under control. But at that point it was too late. Mosquitoes love filth and swampy climates, making New Orleans the perfect breeding ground for these disease carrying insects.

That mask that Doktor Schnabel von Rome wore must have been a doozy!

Filled with Juniper, amber, lemon balm, spearmint, camphor, cloves, myrrh, roses or balsam.

His tenure was during the Plagues of Europe

My grandfather was born there in 1858..he had an older brother and sister..His parents were probably newlyweds at the time of the worst epidemic. They lived at 330 Magazine when he was born but had been in New Orleans since my great grandfather was born in 1814. His father was a small retail merchant with a shop in the city. I wish I knew more. The merchant is listed in the 1852 City directory which I found at the NOLA library.