Tucked away between two parking lots behind the Canal Place mall, not far from Harrah’s Casino, is a white obelisk scrawled with the ghost outlines of some old graffiti and featuring a placard stating, “In honor of those Americans on both sides of the conflict who died in the Battle of Liberty Place. A conflict of the past that should teach us lessons for the future.”

It is likely that most younger residents of New Orleans have never set their eyes on the monument, much less heard about the Battle of Liberty Place, and for a typical French Quarter visitor looking to do some shopping on Canal Street or gamble at Harrah’s Casino, it is beyond obscure. But we can suppose there is a chance one might wander through the parking lot, read the placard, and from that statement infer that the battle must have marked some terrible moment in New Orleans history many years ago and that we have learned from past mistakes and remember them with a bleak white obelisk. It might also be easy to believe that somehow during the development of the city the monument was forgotten and not intentionally hidden. While this might seem true on the surface, a brief investigation into certain bits of The Crescent City’s less shining moments will prove otherwise.

It is likely that most younger residents of New Orleans have never set their eyes on the monument, much less heard about the Battle of Liberty Place, and for a typical French Quarter visitor looking to do some shopping on Canal Street or gamble at Harrah’s Casino, it is beyond obscure. But we can suppose there is a chance one might wander through the parking lot, read the placard, and from that statement infer that the battle must have marked some terrible moment in New Orleans history many years ago and that we have learned from past mistakes and remember them with a bleak white obelisk. It might also be easy to believe that somehow during the development of the city the monument was forgotten and not intentionally hidden. While this might seem true on the surface, a brief investigation into certain bits of The Crescent City’s less shining moments will prove otherwise.

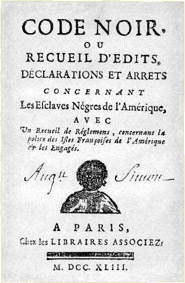

Before we can discuss the Battle of Liberty Place, we need to go further back. From 1719-1731, 5,000 people from the West Africa Senegalese region were imported to New Orleans, as slaves. This was the first of two major waves of importation of slaves directly from Africa. Due to this influx of slaves, the Colonial government applied the rules Louis XIV had dictated for the West Indies: fifty five laws regulating how slave owners had to treat their slaves.

These laws were called Code Noir de la Louisana. Code Noir, like any laws governing slavery, were inhuman, but they did afford slaves in the colony certain rights not afforded to them in Anglo-American colonies. According to Code Noir LIV: “We grant to manumitted (slaves freed from their slavery) slaves the same rights, privileges, and immunities which are enjoyed by free-born persons. It is our pleasure that their merit in having acquired their freedom, shall produce in their favor, not only with regard to their persons, but also to their property, the same effects which our other subjects derive from the happy circumstance of their having been born free.” Consequently, racial relations and identity were much more complex in French colonies compared to Anglo-American colonies.

What was often the case was a slave owner desiring to save money on skilled work (carpentry, masonry, etc.) would buy slaves with the skills they needed or train them in the skilled work. If the master was not cruel, the slave could take these skills and earn money on Sundays. By Code Noir law all slaves (and everyone in the colony) had Sunday off. Many slaves took advantage of these laws to earn money on the side by putting their skills to work on Sundays. Though it was technically illegal for anyone to work on Sundays, colonial officials did not strictly enforce these rules.

The population of free people of color was much higher than in any other city in the Americas. Not only had some slaves been able to buy their freedom through the practice of coartación or self purchase, it was also common practice for slave owners to free slaves in their will. It was also common for slave owners to engage in sexual relations with free women of color in a recognized extralegal tradition know as Placage. The children of these sexual encounters often had access to their father’s wealth, privilege and education. What developed in the colony was a stratification of the African American population based on class, culture and income. “Whiteness” either in appearance or in culture were highly valued with corresponding access to wealth, privilege, and political power.

These factors meant that by the 1840s, New Orleans had a sizable population of free people of color speaking French and holding middle and upper-class positions and controlling several skilled professions. It is interesting to note that the free women born to wealthy free people of color were raised much like the women of white families; that is, trained to please a wealthy man who would shelter her from the difficulties of life. But unlike their white counterparts, women of color could not marry white men. Instead, in a true New Orleans style, balls were thrown where free women of color could meet white men and become their formal mistresses. The women of color usually received living quarters and expenses in exchange for sleeping with the white men on a regular basis. The Civil War ended these traditions.

In 1862, the city of New Orleans was the first city to be occupied by the Union during the Civil War. Union General Benjamin Butler refused to return slaves to their former owners, declaring that they were “spoils of war.” Slaves from all over the south flooded into New Orleans seeking their freedom from slavery. This is the beginning of the end of the system of chattel slavery that had been the rule of law in New Orleans and the rest of the south for so long. Race relations changed drastically at the close of the Civil War as the Reconstruction government was implemented. Hundreds of years of structured and deeply stratified culture was swept aside. No longer were the interests of free people of color separate from the interests of the rest of the black population as all people of color were a threat to white supremacy.

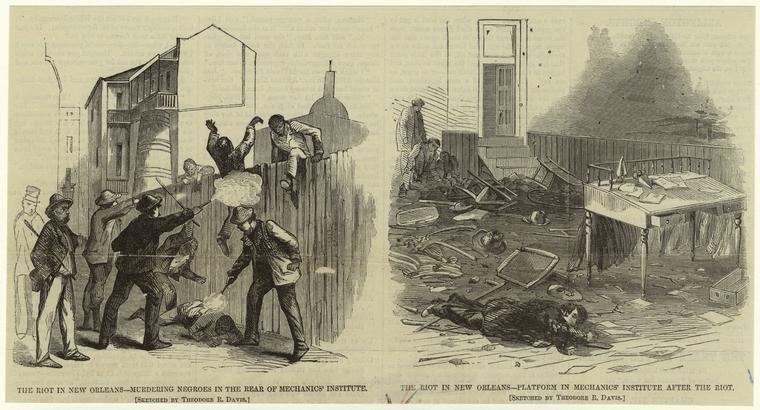

A pivotal moment and a precursor to the Battle of Liberty Place occurred in July of 1866. Blacks, many who had been members of the Union Army, met on the steps of Mechanics Institute at Dryads and Common to protest the lack of voting rights for Blacks in the convention of 1864.

They were met by a force of white mostly ex-confederates. In the riot that followed, 238 people were killed including many former Union Soldiers. In the backlash that occurred, many northerners voted for republicans in the election of 1866 who went on to pass the Reconstruction Act in 1867. This allowed any adult male, black or white, to vote as long as they signed an oath stating they never voluntarily aided the Confederacy. In the election of 1868, the polls were opened for the first time to former slaves and free people of color; many of the free people of color ran and won elections. With the threat of years of white supremacy coming to an end with former slaves having voting rights and holding a majority in the state of Louisiana while former Confederate soldiers and planters were not allowed to vote, many of these men formed paramilitary organizations to defend what is ultimately a continuation of white supremacy. The most notable of these organizations held the particularly menacing sounding name of The Crescent City White League. The Crescent City White League was formed by upper class Democrats from exclusive male social clubs such as the Pickwick and the Boston Club, and their goal was to unite White New Orleanians behind violent resistance to black voting rights using the specter of white supremacy.

New Orleans, with its major population of middle and upper class free people of color was the major seat of power for the Republican government and home to the combined forces of 4,000 soldiers, an integrated State Militia and Municipal Police led by a former Confederate general James Longstreet. These forces were the only local opposition to the Crescent City White League. Longstreet was the only former Confederate general to join the Republican Party. This was an extremely unpopular move. He was considered a scalawag, that is, a southern white who joined the Republican Party, an integrated party that at the time sought power through the black vote. Interestingly enough Longstreet was not the only former Confederate general who believed in voting rights for blacks. There was P.T.G. Beauregard, a former Confederate general who was active in the Reform Party, a group of wealthy white New Orleanians. The group supported the need for voting rights for former slaves, believing that if properly educated, they would vote for fellow southerners on the Democratic ticket opposed to the mostly northern Republican Party.

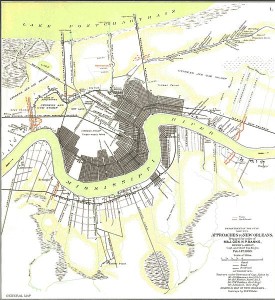

This takes us to the “Battle of Liberty Place,” as it was coined by its supporters. The battle was essentially a coup attempt by the Crescent City White League. On September 14th 1874, Longstreet had gotten word of a shipment of weapons heading to the Crescent City White League. In an effort to stem the violence of white paramilitary organizations against elected officials and blacks, he attempted to seize the weapons at the pier where Canal Street meets the Mississippi river. As the battle commenced, members of the Crescent City White League attacked and captured Longstreet. The State Militia and Municipal Police force fought valiantly but were outnumbered by at least two to one.

This takes us to the “Battle of Liberty Place,” as it was coined by its supporters. The battle was essentially a coup attempt by the Crescent City White League. On September 14th 1874, Longstreet had gotten word of a shipment of weapons heading to the Crescent City White League. In an effort to stem the violence of white paramilitary organizations against elected officials and blacks, he attempted to seize the weapons at the pier where Canal Street meets the Mississippi river. As the battle commenced, members of the Crescent City White League attacked and captured Longstreet. The State Militia and Municipal Police force fought valiantly but were outnumbered by at least two to one.  They retreated to the Customs Building and the Crescent City White League took over the city until federal reinforcements arrived 3 days later. The battle broke the back of the Municipal Police department and the State Militia, the only local force in opposition to the Crescent City White League.

They retreated to the Customs Building and the Crescent City White League took over the city until federal reinforcements arrived 3 days later. The battle broke the back of the Municipal Police department and the State Militia, the only local force in opposition to the Crescent City White League.

In 1877, the newly elected president, Rutherford B. Hayes, withdrew federal protection of black voting rights and of the democratically elected Republican officials. Former Confederate officials and planters took control of the state and city government by force and installed one of the most repressive and racist governments in the country. Part of the propaganda of the new government was that The Battle of Liberty Place was a glorious moment in southern history, a moment where heroic and valiant citizens stood up to a corrupt government of northerners, the irony being that the government installed was considerably more corrupt and anti-democratic. An annual commemoration of the 1874 uprising was marked by a solemn pilgrimage starting at Canal Street and ending at the gravesites of members of the White League. Units of the State Militia would retrace the route of the White League actions of ’74 and end at the river for a 21-gun salute. As the years went by, the memory of the event and the myths surrounding it faded until it was a waning tradition.

This changed in 1891. An ongoing war between two Sicilian families for the control the riverfront ended in the slaying of the chief of police. A wave of anti-Italian sentiment gripped the city, and 250 Italians were arrested. Eleven were eventually charged with the murder but acquitted for lack of evidence. The Veterans of the White League called for a mass meeting and on March 14th, a huge crowd gathered on Canal Street. It was there the gentlemen of the White League agreed with the crowd that something had to be done. After a visit to a nearby gun store they set out to do “justice” at the Orleans Parish Prison by dragging the eleven recently acquitted Sicilians out of their jail cells and shot or hung them.

This event revived interest in the uprising of 1874 and secured enough donations to erect a monument. In 1891, an obelisk shaped cement monument was placed at the foot of Canal Street, in the heart of downtown, and dedicated to the fallen heroes and leaders of the 1874 uprising.

To add insult to injury, in 1934, the city took Works Progress Administration funds and added a plaque stating “United States troops took over the state government and reinstated the usurpers but the national election in November 1876 recognized white supremacy and gave us our state.” On the opposite side appeared, “McEnery and Penn, having been elected governor and lieutenant governor by the white people, were duly installed by the overthrow of the carpetbag government, ousting the usurpers Gov. Kellogg (white) and Lt. Gov. Antoine (colored).”

This was no coincidence; the plaque was added on the fifty-year anniversary of the event and in a time when the Governorship of populist Huey P. Long threatened to overthrow the powers of the white elite who had ruled New Orleans since Reconstruction ended. The plaque and the ceremony surrounding its installation were an attempt by the mayor to rally political and popular support against the governor.

With the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, African Americans were once again allowed to take part in democracy and in a city with a majority African American population, they became a major political power in New Orleans. Consequently, Moon Landrieu was elected mayor in 1970 with 90{bcd54f9804855276c8678e686ad999f26fd67ea610b58b5a8c95101747e2c9d5} of the black vote. This was due to his voting record as a State legislator in which he voted against 29 segregationist bills in 1960. He understood the meaning of symbolic actions, especially when it came to historic monuments in a public place, but he did not want to anger the white preservationists who formed his uptown power base. He created a compromise, the placement near the monument of a brass plaque describing the battle as an “insurrection” and noting that the controversial language carved on its base had not in fact been part of the original 1891 monument. Most important, no doubt, was the plaque’s additional message that “the sentiments expressed are contrary to the philosophy and beliefs of present-day administration of New Orleans,” In this way he could satisfy the majority of his constituents by distancing himself from previous white administrations but not anger those who feared the monuments removal as a loss of history.

In 1977, Ernest “Dutch” Morial became New Orleans’s first black mayor. As a former civil rights lawyer in New Orleans, he was used to standing up to the city’s established social oligarchy and he refused to bend to their orders regarding this particular monument. He attempted to quietly remove the monument once and for all arguing that “this monument, because of what it symbolizes, has long been a source of divisiveness in our community. The sentiments expressed in the inscription and by those who on occasion use this as a rallying point are not consistent with the principles of liberty, equality and justice that are the cornerstones of our society.” The city council disagreed and prevented him from doing so. The city council passed an ordinance forbidding the removal of any monument without its consent. A compromise was reached allowing the removal of any offensive wording, so the plaque added in 1934 was covered by blank granite. The idea was that this returned the monument to its original non-racist context but it ignored its historic use as a rallying point for white supremacy. The City Council attempted to separate the monument from its history in order to save it.

In 1989, under the administration of the second black mayor Sidney Barthelemy, the monument was removed during renovations to Canal Street. This began over three years of public debate, negotiation and legal actions. The passing of The Historic Preservation Act of 1966 increased the federal government’s ability to oversee historic sites all across the country. State officials in conjunction with local preservationists used this act and determined that the monument fit the criteria for inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places.

This involvement prevented the city government from acting on its own because the criteria for the monuments removal hinged on an agreement with the federal government and state agencies to re-establish the monument near the original event the monument memorialized. Mayor Barthelemy argued against placing the monument in its historic location due to traffic concerns and the planned development of Canal Street, not mentioning its historic context. The city council and the Mayor stalled for several years until the federal government forced their hand to chart a course between various extremes.

On one hand there was the “Friends of the Liberty Monument” who attempted to argue for the monument’s historic merits, stating it was necessary for future generations to never forget their past. Then there was former KKK wizard David Duke who had used the monument as a rallying point for his white supremacist rallies and who not only wanted to preserve the monument in its historic location at the foot of Canal Street but wanted to maintain the 1934 text additions.

On the other hand, there were activists who felt that what the obelisk symbolized could not be changed and in the words of Dr. Cassimere, a professor at University of New Orleans, “A monument to white supremacy in modern America occupies the same position that public statues of Lenin and Stalin did in post communist Russian. The most visible reminders of a discredited regime, the Russian people turned into gravel, they neither preserved nor celebrated these monuments as reminders of an untouchable part of an imagined glorious past.”

The city’s legal commitment was to reestablishing the monument in a public place near the historical event. Yet, the unwillingness of state officials to place the monument in a museum blocked the city from the option that most of the public agreed was the best solution: install the monument in a museum where its historical context could be explained.

In March 1993, after years of debate and stalling, the city returned the monument to a public space. They were limited in their choices of relocation. The new site had to be within a several blocks of the original location. They picked the most obscure site possible: on Iberville Street with a combined parking garage and mall between in and Canal Street and next to two more parking lots and on the backside of the city’s aquarium and riverfront train tracks. It remains in the public space but it is nearly hidden from public view. Thus they followed the letter of the law and ended the legal battle.

They weren’t necessarily spared controversy. On May 30th 2004, David Duke planned a rally at the monument’s new location. In reaction, the night before the planned rally, the monument was covered in anti-Nazi graffiti and David Duke canceled his rally. More recently, on March 27, 2012, in response to the deaths of Trayvon Martin, Justin Sipp, and Wendell Allen the statue was again covered in graffiti. An anonymous communique stated:

We mourn these young mens’ deaths and strike out in retaliation against the system that brought them about. The system that celebrates slave owners and racist lynch mobs is the same system that exonerates killer cops and racist vigilantes. We want memorials to these fallen innocent youths, not to slave owners and racist mobs.

History has always been interpreted, simplified, and manipulated to fit the needs of those in power or those seeking to gain power. Monuments glorifying moments in history provide a symbolic gesture of their power, a rallying point, a way for them to connect themselves to the glorious past. Liberty Place therefore is a great example of a monument built to exemplify white supremacy, a rallying cry for post reconstruction politicians to unite divisive whites against the hated other. It should come as no surprise to anyone that as soon as blacks gained civil rights in the 1960s, that there would be a growing movement to destroy the monument, but the move to destroy symbols of racism bring out overt and covert racism. As a compromise, Mayor Barthelemy chose to move the monument to an obscure and forgettable place. Despite our elected officials’ desire to forget the past, there is a growing grassroots movement by African Americans to preserve their history. For one small example of this check out Edward W. Louis’s excellent article about the 1811 slave revolt in the Louisiana Weekly. It goes to show that the fight against white supremacy and racism is more then theoretical but real and often made of stone.

Bibliography for further reading

Wagner, Jacob. Race, Public Memory, Civil Rights and The Liberty Monument in New Orleans (written for government)

Powell, Lawernce. A Concrete Symbol. Southern Exposure VoxuIII No 1.

Wall H Bennett, Cummins Townsend, Schaifer, Haas, Kurtz. Louisiana, A History fifth edition. Wheeling: Harlan Davidson, 1990.

Foner, Eric, Forever Free, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005

Du Bois, W.E.B, Black Reconstruction In America 1860-1880, New York, The Free Press, 1998.

Asbury, Herbert. The French Quarter an informal history of the underworld, New York: Garden City Publishing, 1938.

Lewis, Edward, New Orleans: The Struggle for Recognition of the Historic 1811 slave revolt The Louisiana Weekly

Reed, adolph Jr. The battle of Liberty Monument, the progressive June 1993

Basically no person may well be worth an individual’s cry, as well as an individual that is actually been successfull

I’m extremely inspired along with your writing skills and also with the format on your weblog. Is that this a paid subject or did you customize it your self? Either way stay up the nice high quality writing, it’s rare to look a great blog like this one these days..