The Louisiana Supreme Court Building: Lessons to be learned from a Beaux-Arts Monstrosity in the French Quarter

By Nora Goddard

The full version of this article is available as an book

The full version containing illustrations, citations and the site’s chain of title is available as an ebook here

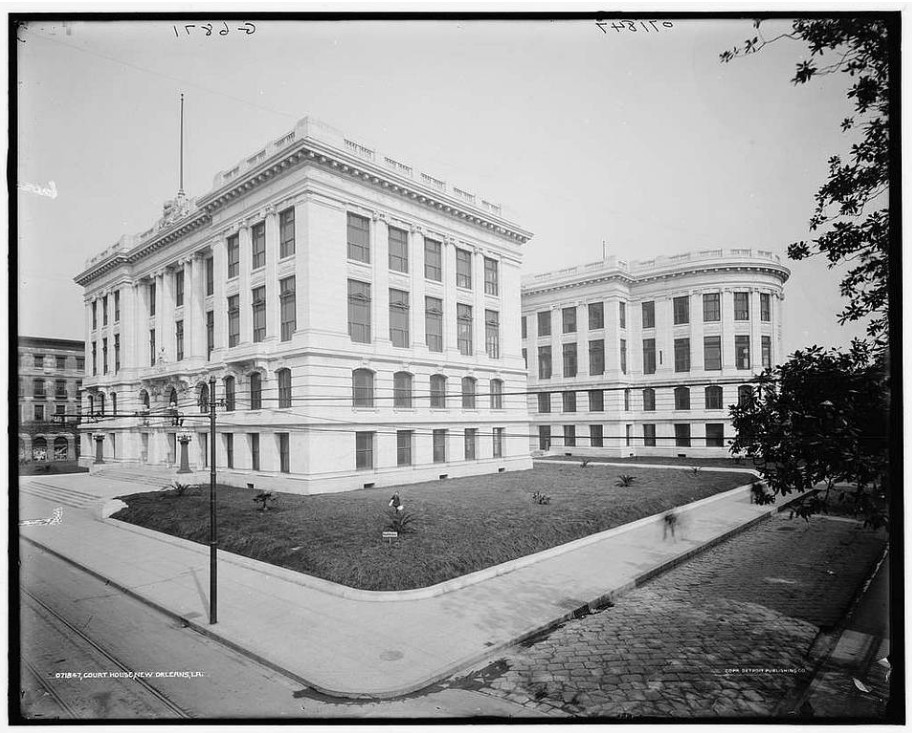

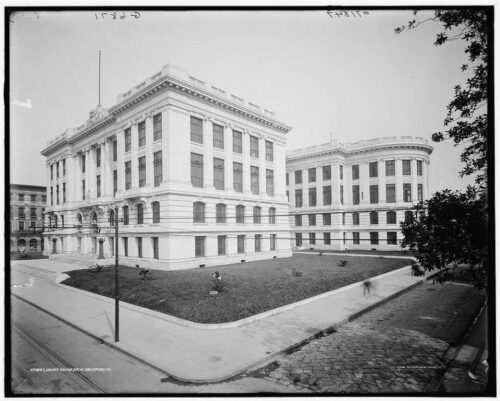

The Louisiana Supreme Court building, a hulking Beaux-Arts marble monument, is an architectural anomaly between Royal and Chartres Streets, in a corner of the French Quarter densely packed with late 18th and early 19th century masonry and stucco buildings. The site has an intriguing past. The Supreme Court first convened not here, but nearby in the Presbytere. In 1804, after the purchase of the Louisiana territory by the United States, the Superior Court of the Territory of Orleans, the court of the colonial French tradition, was transformed into the Louisiana Supreme Court. The new court was convened for the first time in 1813. The Court was housed in the Presbytere from this time until 1862, when confederate New Orleans was taken by Union troops. For six years the court was held in Shreveport, before being moved back to the Vieux Carre, this time in the Cabildo. It was housed in the Cabildo until 1901, and during this time heard

many important cases, including the famous segregation case Plessy V. Ferguson, and the Myra Gaines Case, the longest running lawsuit in American history, over women’s rights to inherited property.

As far back as 1891 the need for the court to have its’ own building was known. This was expressed in a Times-Picayune editorial article, which pled, “it is urgent that something be done by the present municipal authorities to give New Orleans its first modern courthouse.” In 1898 prominent members of the Louisiana Bar Association united to lobby the Louisiana Legislature for the cause. The Courthouse Commission was established by legislature in 1902 to oversee acquisition of a new courthouse site for both the Supreme and Civil District courts.

Albert Anthony Ten Eyck Brown and Philip Thornton Marye

In 1905 newspapers nationwide advertised a competition for design of the courthouse, with prizes of $5,000, $2,500, and $1,000 for the first, second, and third place winners. Only two designs were submitted by local firms, and neither placed. Albert Anthony Ten Eyck Brown and Philip Thornton Marye from Brown, Brown & Marye of Atlanta won the competition.

The firm had created courthouses and other public use buildings, many in the Beaux Arts style that the city wanted for the Supreme Court Building. A dramatic revivalist, Marye designed Atlanta’s railroad terminal in the Renaissance Revival style, and Birmingham’s in the Byzantine Beaux Arts style. He built the Beaux Arts State Administration Building in Raleigh, of which the Georgia Encyclopedia writes, “[it] exemplifies his subtle handling of neoclassical elements to set a monumental building in a tight urban site.” Similar qualities can be seen in the Royal Street Supreme Court building, such as the subtle scaling back of the front façade to allow more space before the sidewalk. He met Brown in Atlanta and formed their firm which would win the 400 Royal St. design competition the following year.

Albert Anthony Ten Eck Brown designed the Fulton County Courthouse and the Clarke County Courthouse in the Beaux Arts Style. He’s famous for his majestic theaters such as the Forsyth Theatre in Atlanta. Brown is considered to have set the standard for stripped down “depression classical” public buildings, such as his 1932 Thornton Building.

Their firm’s later projects included the First National Bank in Dublin Georgia, and the Miami-Dade County Courthouse, the tallest building south of Baltimore until the 1930’s. They designed St. Luke’s Episcopal Church in Atlanta 1906 in the gothic revival style. Marye became active in the Commission for the Preservation of Historic Buildings in America, creating an archive of Georgia’s landmarks with his photos and sketches. He was also a district officer for the Historic American Buildings Survey in the 1930’s. Brown was supervising architect for a group of Italian Romanesque revival public school buildings in Atlanta. He also designed the interesting Arlington Hall, a reduced scale replica of a Virginia mansion. Intended to be part of Lanier Baptist College campus, the building now stands abandoned in the suburbs of Atlanta.

The Beaux-Arts Style

The French Beaux-Arts school’s focus on history caused it to figure prominently in the early preservation movement in France. Ironically, when transferred to America the style became one of the predominant forces in destruction of the historic fabrics of American cities. American architects at the turn of the century were seduced by the stately, masculine French interpretation of Roman architecture, and began a trend of building many public buildings in this style. Beaux-Arts style buildings led small towns and struggling city centers a sense of importance and authority derived from their perception of the more established European cities. It has been cited as a kind of “cultural inferiority complex,” a deep seeded belief that all admirable culture and design comes from Europe. This trend, and the Beaux arts movement in general, was fueled enormously by the influence of the 1893 Colombian Exposition at the Chicago’s World’s Fair. The fair was a huge show of power for the rising Beaux-Arts movement, and the new way of thinking about urban planning that was a part of it. Cities across America began attempting to remodel themselves to resemble Paris, or Rome, or sometimes their rather whimsical perception of these places. This is known as the City Beautiful Movement. It usually involved slum clearance and other “social hygiene” actions. The buildings resulting from it typically use the most expensive materials such as marble, copper, brass, and large amounts of sculpture and ornament.

Where Beaux Arts buildings do exist in Louisiana they are a minority and stand out starkly, having a huge visual impact. Some examples of this would be Theodore Link’s plan for the LSU campus in Baton Rouge, which was altered later, and the Air Force Base in Bossier City.

Construction of the Courthouse

The cornerstone for the Royal Street courthouse was laid in 1908 with a grand ceremony. Construction was finally completed in 1910, at a total cost of over a $1,350,000 dollars. As well as the Supreme Court, the building also originally housed the Law Library, the Board of the Port Authority, the State Board of Health, Orleans Levee Board, the Dock Board, the Constables office, Notarial Records, Tax Collector, the Court of Appeals, Civil and City Courts, the Oyster Commission, and the Attorney General. Attempts to consolidate all government office.

The building is typical of the Beaux Arts style in that its design follows its’ function, which is to consolidate and house the civic government office of New Orleans. It also typifies the style in its’ classical portions and imposing stature. It’s not surprising that this style was chosen, for it was preferred almost nationwide by city officials desiring to glorify the image of their city. A 1906 Daily Picayune article announced the building was “to be modern in every particular.” It has the stately classical proportions to be expected in the style, with expensive marble on the entire exterior, and terra cotta cornices that had to be specially imported. It is indeed monolithic, and its’ decoration inside and out is ornate.

Of all the places in Louisiana an enormous Beaux Arts building would possibly be appropriate, the French Quarter in New Orleans is possibly the worst one. Lyle Saxon describes the building in his 1938 New Orleans Guide Book as ‘an unwelcome intruder in the French Quarter” (Cangelosi 11). He was not alone- in a 1926 article in The Journal of the American Institute of Architects entitled “Speaking of Ugliness,” Whitaker wrote, “Viewing it again after the lapse of years I am struck anew with the fact that it is probably the most monstrously ugly building that man has ever had the hardihood to inflict upon a suffering earth.”

He reiterated his point in 1934 in the book Ramses to Rockefeller, where he described the courthouse as “one of the worst examples of public building to be found in all America. Never was there a greater absurdity than dragging marble to New Orleans to build a bounder of a courthouse, right on the road to Jackson Square and almost in the heart of the Vieux Carre.”

There was much public unhappiness about the construction of the building. The lot it sits upon was one of the oldest in the city. The chains of title show that almost all the inhabitants could trace their titles all the way back to 1803, when they were “acquired in the succession of Joseph Dusuau de la Croix”. De la Croix’s family, the Le Blancs, were some of the first Acadian exiles to emigrate to Louisiana from Quebec in 1772 and some of the first to inhabit the French quarter, what was then the city in its’ entirety. Henry C. Bezou, the archdiocese of New Orleans Catholic Schools in the 1960’s, said this block was, “among the most historic in the entire Mississippi Valley. De La Tour’s plan, dated January 1, 1723, shows the first clearing for our city at the foot of Canal Street.” Although the properties were deemed “blighted” by the city, they were described by one writer as “the finest examples of old Creole residences” in the Vieux Carre.”

There was one particular structure on the block that was extremely historically significant, and there was much to-do about it getting torn down. This was 406 Royal St, at the time the residence of writer Mollie Moore Davis. The house was once owned by Edward Livingston, who had allowed the use of it to Andrew Jackson to draft his defense plans for the Battle of New Orleans in 1815. This beautiful building was so beloved by the daughter of a prominent New Orleans family, that she arranged for it to be demolished last so that she could be married there, her lifelong dream. The Café des Colonnes, a beautiful building designed by De Puilly was lost, as well as the famous pharmacy of A. A. Peychaud. In an 1834 newspaper ad he announces that he The Café des Collones in notarial archives has purchased the drug and apothecary store on Royal between St. Louis and Conti. Peychaud made the world famous Peychaud’s bitters, still used by virtually every bartender in New Orleans, and is also credited with inventing the Sazerac, the world’s first “cocktail.”

Historical Context – Urban Renewal in the French Quarter

Today these historical and cultural connections are lauded, but at the time the Vieux Carre at this time was considered an “immigrant slum,” with parts of upper Royal St. seen as the worst part of it, according to writings by architectural historian Robbie Cangelosi. Period photos do show most of the buildings on the block to be in need of maintenance, but now we can see that the handmade signs and tightly packed townhouses typify the Creole style, even if they are not immaculate, and that much of the disparagement of the area could have been attributed to xenophobia. At the time of demolition the forty-one buildings on the block housed about two hundred people, mostly renters and boarders. The population was not only dense, but ethnically and racially diverse, perhaps another “undesirable” element to planners at the time. To obtain the land needed for the courthouse, several properties were expropriated by the city, with no mention of compensation. Others, such as 424-426 Royal St., were purchased by the city for as little as $1,500 each, a pittance even for the time.

There were early preservationists such as Nina King, whose photographs are the last record we have of these old buildings. In general, preservation was not a concern at the time and there were no regulations in place to stop demolitions like this. Due the “City Beautiful” movement, there was a fierce desire to revitalize cities at this time. It was deemed absolutely necessary to build the new building, and the Cabildo and Presbytere, today beloved historic structures, were then described as, “Relics of the olden days and are altogether unsuited for the purposes to which they are devoted. They are dark, damp, and dingy.” At the cornerstone ceremony in 1908 Henry dart would again describe the Cabildo and Presbytere as “chilly and unhealthy caverns.” Even renovation was sneered at. It was proposed that the old Hotel Royal be renovated for the courthouse, until the Times-Picayune printed the findings of Henry P. Dart, who had inspected the building, declared that “the building is of no value whatsoever…it would have to all be replaced.”

This time of urban renewal changed the look of this part of the French quarter drastically. In 1918 the famous St. Louis Hotel was demolished by order of the Health Authority, and the following year the French Opera House burned. A visitor returning to New Orleans in the 1920’s after a period of absence proclaimed, “the changes wrought by modern American life seem quite disastrous”. Of the courthouse he said, “The splendid and costly building of shining white marble forms a strange contrast with the noble simplicity of the old banks building opposite, an arrogant parvenu [nouveau riche] in the midst of proud though impoverished aristocrats.”

Documents in the Orleans Parish Clerk of Court’s Notarial Archives lament, “the old buildings that stood upon the site were among the most interesting and historic in the Vieux Carre, all thoughtlessly demolished in a day which had not yet learned to appreciate the tremendous value to the city whose tourist trade is now second only to its port.”

The size and lavishness of the building made expense a huge issue and transformed the project into a bureaucratic debacle from the very beginning. The Times-Democrat reported on Sept 1, 1909 that the courthouse was completed, but no attempts to acquire furniture had been made. On Sept 1, 1910 they reported that the furniture had been acquired, a full seven years after the demolitions of the sacrificed buildings had begun and the court had become unhoused.

Midcentury Decline and Restoration of the Courthouse building

Despite its’ huge expense, by the 1930’s the building had already begun to deteriorate, and in 1935 had to have its’ entire roof replaced at a cost of over $25,000, as well as repairs on the plumbing, elevator hardware, and cornices. (Cangelosi 11). In 1957 the city of New Orleans sold the building to the Department of Wildlife and Fisheries for $1,100,000. Despite efforts by Senator Robert Barham to have the court moved to baton Rouge, it stayed in new Orleans, its’ historic location, due to New Orleans larger airport and more active legal network. The Louisiana Supreme Court moved to its new home in Duncan Plaza near City Hall, while the District Court and Court of Appeals leased space in 400 Royal from 1962-1976. Other temporary tenants would include US Bureau of Fisheries, Bureau of Forestry, Dept. of Agriculture, state Fire Marshal, Department of Conservation, Louisiana Department of Labor, Occupation Standards, and Public Works.

During this time, the Department of Wildlife and Fisheries only occupied the first floor of the building, using the rest for storage of taxidermized animals and other artifacts. The building fell into extreme disrepair during the following decades. By the time the Wildlife and Fisheries vacated it in 1981 the building was in such bad shape that twenty-five water drums were placed around the building to catch leaks from the roof, which had a healthy crop of trees growing on it. A maze of extension cords wove between the drums of water to power parts of the building still in use, and it was not unusual to find homeless people squatting in the abandoned courtrooms on the upper floors. Enormous marble blocks from the upper floor ornaments would occasionally crash to the sidewalk, threatening to crush pedestrians.

The building, loathed by many even when it was new and shiny, was now considered by almost everyone, except maybe the squatters, an eyesore and blight upon the French Quarter. Discussion began for what to do with the enormous building. Many groups supported the transformation of the building into an opera house. These groups included the Women’s Opera Guild, the LA Council for the Vieux Carre, the NO Opera Club, and the Greater New Orleans Opera Foundation. Harold Shea of the Cultural Attractions Fund also praised the idea, saying “no adequate state auditorium for the presentation of cultural programs” existed in New Orleans. This lack of fine arts venues had been unremedied since the 1919 destruction by fire of the French Opera House. Many Vieux Carre residents were uncomfortable with the idea of a courthouse in their neighborhood, fearing the presence of “undesirables,” despite the fact that most of the offenders would be attending court for traffic fines. Ominous predictions were made of unsavory characters robbing and terrorizing the honest citizens of the French Quarter. One citizen prophesized “hangers on by the dozen lounging for a year or more on the portico and grass,” a dreadful fate for a district so historically pure of crime and sin. Many saw an opera house as a much needed dose of high culture in the highly vernacular French Quarter. A May 10, 1963 States-Item article reported that house Bill 56 was filed to convert the building to an opera house and awarded 2 million for renovations. It was later killed in the legislative session.

Other proposed uses for the block included casino, tourist center, movie set, park, and parking lot. The Vieux Carre Commission recommended in 1962 that it be torn down, having no architectural merit. In an attempt to solve the controversy, Roger Ogden was asked by Governor Mike Foster to be a consultant on the use of 400 Royal. His opinion was that it was best to renovate it to again house the Supreme Court, as well as the 4th circuit court and the law library. In 1980 the Vieux Carre Commission reversed its’ original statement, deciding that the building was worth saving and preserving, a reminder of how quickly our views on what is valuable can change. In 1984 plans were announced to move the court back into 400 Royal St. The original date for relocation was set for 1987, but these plans would not come to fruition until 2004. Justice James Dennis and others in the legal scene took it upon themselves to lock up antique door knobs, chandeliers, and other artifacts while the building was unoccupied. They discovered dozens of oil paintings in the basement, rotting into oblivion. There were over 60 portraits of Supreme Court justices, dating back to the early 19th century. Today these have all been restored and hang in the walls of the courthouse, though they surely would be destroyed if these citizens had not intervened.

In 1991 the local firm Lyons and Hudson was hired to be in charge of the renovation to facilitate the return of the Supreme Court to the building. Lyons and Hudson had also successfully renovated the Orpheum Theater, the Touro Synagogue, and the Howard Tilton Memorial Library at Tulane. They began renovation in 1993, an enormous undertaking as the building was literally falling apart. Unlike the practical, weather resistant Creole residences that have survived in the French Quarter for hundreds of years, this feat of vanity cost a fortune to renovate when it was less than a hundred years old. The sheer size, and the pretentious choices of materials would have made it impossible to renovate exactly how it was, but the firm was careful and thoughtful in their changes. Their 1999 blueprint shows that much of the ornamental cornice was missing, or heavily damaged by plant growth. It shows they added many details that while not original, are fitting in the original beaux arts style, including brass handrails and doorknobs, and beautiful art deco light fixtures indoors and out. They used resilient modern materials to repair the long-suffering cornices. Much of the terra cotta work was replaced with plastic, though it is indistinguishable from ground level. (Justice 65) Some light fixtures and some furniture, including the judge’s benches, is original to the building. The wrought iron fence is a replica of the design on the interior grand staircase. Originally interior friezes featured fasces of an ax protruding form a bundle of willow rods bound with a red strap. These have been changed to olive leaves. The architects chose to leave the grand entrance spaces intact but lowered the ceilings in work areas and laid down carpet. The ceiling height rises a bit each floor you go up, with the exception of the mezzanine, which feels like an unnecessary, vacuous space. The courtrooms retain their original dark wood paneling and imposing canopies over the judge’s seat. The naturalistic landscaping around the building, and the subtle renovations, actually allow the building to blend into its’ surroundings more effectively than it appears to have originally.

The Supreme Court finally moved back to the building in 2004. Today the building houses the rare book room and the Louisiana Law Library, as well as the Supreme Court and a museum about the history of the building. The rare book collection includes many original colonial legal documents, including the 1587 text “The Seven Parts of Law”, and the 1804 “Code Napoléon”, used as the model for Louisiana’s civil code. The rest of the Louisiana State Collection is housed in Baton Rouge. (Rightor)

The story of this building has some important lessons within it. There were no zoning laws in place at the time of the construction of the courthouse. The destruction of the oldest buildings in the French Quarter, as well as other poorly conceived “urban renewal” projects of the 1920’s, ultimately led to the preservation law that we have today in New Orleans, such as the landmark 1941 preservation case New Orleans vs. Pergament (198 La.852, 5 So.2d 129 (La. 1941). In this case about allowed sizes of signs in the Quarter, Justice O’Neill said the following,” “the preservation of the Vieux Carre as it was originally a benefit to the inhabitants of new Orleans generally, not only for the sentimental value of this show place but for its commercial value as well and is in fact a justification for the slogan ‘America’s most interesting city’ (Chadwick 4). This set up the idea of the “tout ensemble,” the importance that the whole, general character of the area is preserved, not just a few select buildings.

An important preservation goal has been achieved with the saving of the courthouse building. This is to maintain original uses of historic buildings, in my opinion the optimum result. This preserves not only the physical structure, but the original interpretation of the building and the space around it. It’s important for historic environments to continue functioning, to prevent them from becoming “boutiqueized,” Disneyland like environments. This contributes to the overall sense of place and history. Says Coleman about the move back, “you will understand the difference between our Louisiana law based on the French Civil Code and the common law practiced in all the other states. When they go to the French Quarter, they will have something they can really see and learn about the history and merit of our law.”

While maintaining original use should be ideal for any building, the ridiculous nature of Beaux-Arts design makes it one of the only logical uses for this building. The floor plan in incredibly complex and counter-intuitive, the original plans showing a multitude of spaces that “serve” other spaces. These include numerous hallways, passageways, entry halls, closets, waiting rooms, and coat rooms. The building would have had to be almost completely gutted to accommodate the proposed opera house, or anything else really except a complex of offices. The somber courtrooms are some of the only hugely impressive spaces in the building, it would be ridiculous to save the building but not save the interior spaces such as these.

In the 1924 case Civello v New Orleans (154 La. 271, 97 So. 440), he said “an eyesore in a neighborhood of residences might be as much a public nuisance, and as ruinous to property values, as a menace to safety or health”.

Menace or not, the courthouse is a unique example of the Beaux Arts style in the French Quarter, and a rare example in the city as a whole. It is in a way a historical stepping stone between the 19th century buildings expected of the French Quarter, and the mid-century institutional architecture of much of the CBD, such as City Hall. The “tout ensemble,” after all, has to be somewhat fluid. The powerful impact of the French Quarter is much more complex than simply recreating an era. It’s cumulative effect includes tourist-centric commerce, public housing, and industrial infrastructure. The downtown districts of New Orleans are wonderful because they are lived in, evolving, not idealistic and not a museum. It was never clean, safe, or homogenous, and it is important to not expect it to be now.

The courthouse is now part of the heterogenous fabric of that environment. James Coleman, law and founder of the Louisiana Supreme Court Historical Society, has written about his fond memories of the courthouse location in the 1950’s. “You would walk down to Royal Street to the court and on the way you’d pass by a gypsy [sic] woman who read tea leaves. She would tell you if you were going to win your case.” In fact, unexpected and illogical cultural relationships is one way you could describe New Orleans culture in general. An important lesson to be learned from the City Beautiful movement is that fascination with trends and styles from other places is often a bad idea. In New Orleans we should focus on the richness of our local cultural resources, instead of trying to “modernize” so much.

Dr. Bernard Lemann wrote about the complexity of the French Quarter architecture, and how it was created to house “the varied types and activities of hucksters and barkers, artists and shopkeepers, showgirls, antique dealers, tourists, evening crowds….how do you preserve a kaleidoscope? Obviously, to keep it, you must keep it in motion.” I agree with this sentiment entirely.