Architectural History of the Garden District

When most people think about New Orleans, they typically think about the French Quarter, Bourbon Street, and Mardi Gras. As important as this is to the character and culture of New Orleans, they often neglect the true beauty of the rest of the city. One only has to hop on a Streetcar heading uptown to The Garden District in order to access these historic and magnificent yet often overlooked areas of the Crescent City

This beauty is perfectly displayed just up the river from the French Quarter, in a historic neighborhood called the Garden District. While the Garden District provides tourists and locals alike with a lovely juxtaposition to the French Quarter, it often gets overshadowed by its more gregarious relative. French Quarter is, for the most part, architecturally homogeneous; exhibiting its original French and Spanish colonial influences. The Garden District, on the other hand, displays a melting pot of “new” architectural styles. One sees a synthesis of British, Italianate, Second Empire, “Greek Revival”, and many other styles in close proximity to one another.

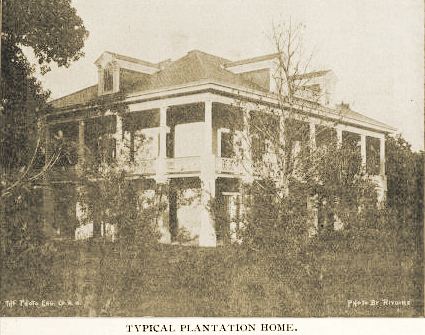

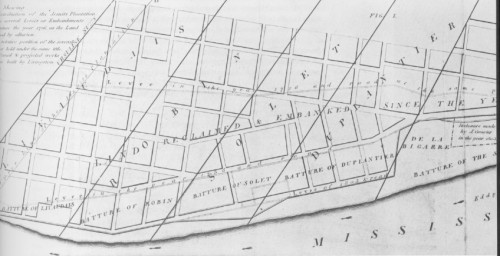

In order to truly appreciate the wonder that is the Garden District, though, you must first understand both its history, and the history of New Orleans. In the early 19th century, while the French Quarter was blossoming into the urban center of a major metropolitan city, the Garden District was still largely made up of plantations, most notable of these was the Livaudais Plantation. As slavery came and went, though, these plantations were sold off in parcels to wealthy Americans who did not want to live in the French Quarter with the original settlers. This area was formerly a part of the city of Lafayette, which was later incorporated into the city of New Orleans.

As the plantations were dissembled to make room for American “carpetbaggers,” Lafayette was redeveloped byBarthelemy Lafon, a notable architect, engineer and city planner. Though he originally laid out what is now known as the Lower Garden District, he eventually improved his plans to include the Garden District. His original plans for these new “suburban” blocks typically included two large residential lots as opposed to the more densely plotted old city.

Instead of the typical working-class style of the French Quarter, Bywater and Treme; the Garden District demonstrated the latest in Victorian elegance. Styles such as “Greek Revival” became popular, which flaunted high ceilings, massive columns and intricate plasterwork. The most notable feature, however, were the intricate and beautiful gardens meant to attract wealthy northern industrialists and petit-bourgeois to the new suburb. It was then that the neighborhood became known as the Garden District.

As the city grew in population and land along the river became more scarce, the original lots were once again sold off in parcels, where late-style Victorian “gingerbread” style houses appeared in clusters. As a result, blocks typically have a mix between Antebellum mansions and late 19th century Victorian style mansions.

The mid-20th century brought about a newer, more typically American-style architecture.Magazine Street, long known as the economic center of the neighborhood, along with St. Charles Avenue, began showing signs of burgeoning commercial development. Commercial buildings, such as New Orleans banks and buildings with smaller, lower roofs began popping up, showing a modern influence that had previously never been seen.

Even with new buildings and the skyline of the modernist CBD in sight, the neighbourhood remains one of the most well-preserved and impressive examples of architecture in America.