When To Take A Seat, When To Make A Stand: The history of 1031-1041 Canal Street, past and present

by D.G.W Hedges and Eric Spinrad

For weeks there was a plan to write a short piece on the history of the corner of Rampart and Canal, the future site of the Hard Rock Hotel. On October 12th, the top 7 floors of the construction collapsed, tragically killing 3 construction workers and injuring 18 others. The situation, while writing this, is still very precarious and parts of the building, along with the construction cranes, threaten to collapse at any moment. Buildings within several blocks have been evacuated and the Saenger Theater, which suffered roof damage, has cancelled the next month of scheduled performances. Cleanup, as well as a multitude of legal disputes, are most likely going to take a long time and the future of the site remains uncertain. Our heart goes out to those affected by this tragedy.

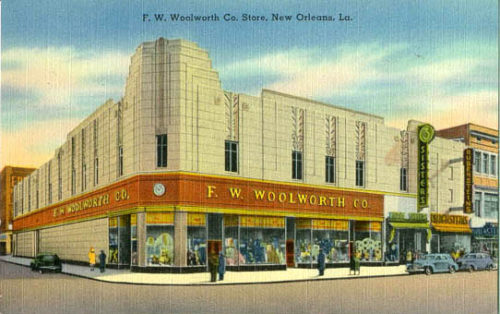

The original article was a look into the mid-century Woolworth’s, which previously existed on the site, when the city was an extremely polarised and different place. In 1960 the building housed the first lunch counter sit-ins, which protested the deep south racial inequalities of Jim Crow laws. Alongside of DH Holmes, Kress, Godchauxs and a slew of other department stores, Woolworths was at the center of shopping in New Orleans. Metairie wasn’t a fully realized suburb yet, with its multiple shopping districts, so much as it was a bunch of farms; white flight had not yet happened, which was in a large part due to the desegregation of schools led by Ruby Bridges and the McDonogh Three (Leona Tate, Tessie Prevost, and Gail Etienne).

Imagine a trip on the St Charles streetcar, off at Canal and Carondelet, drop into one of the many department stores to peruse the latest fashions and then into Woolworths for a bite to eat at the lunch counter before heading back Uptown. Before you get excited and nostalgic about the “good old days”, take off those rose tinted glasses and remember that the mid-century was a time of strict and brutal segregation in the South. While New Orleans was (and is) different (link to creole), it was not immune to the Jim Crow South.

The shops on Canal were, for the most part, owned by wealthy white uptown protestants and while African Americans could and did shop along Canal, it was under an unwelcoming glare and exclusion from many of its dining establishments. At the time there was another shopping district on Dryades in Central City that was largely owned by New Orleans’ Jewish community; Canal street was as unwelcoming to Jewish merchants as it was to Black customers; Dryades filled the void of both, though neither Canal or Dryades’ shops would offer African Americans employment.

Much changed in the Post-War landscape of the United States. Black veterans returned home from fighting overseas (in segregated units) and found many jobs closed off to them, leaving them in turn locked out of the post-war economic boom. A large result was a growing Civil Rights movement across the United States where African Americans began to organize around religious leaders with churches being central in the fight for equal access to work and the desegregation of public spaces.

In 1959, Rev. Avery Alexander, Rev. A.L. Davis (SCLC), and Dr. Henry Mitchell (NAACP) organized the Consumers’ League of Greater New Orleans (CLGNO), to combat employment discrimination by the Dryades Street merchants. One of CLGNOs lawyers, Ernest “Dutch” Morial, would eventually go on to become the first African American mayor of New Orleans. The League first tried to negotiate with the Dryades store owners, but with no progress they decided to boycott the shops on Dryades and form picket lines. Students from New Orleans three major Black Universities (Xavier University of Louisiana (XULA), Dillard University, and Southern University of New Orleans) got involved alongside of some white students from Tulane and Loyola to lead organizing efforts. Good Friday, Easter weekend, found many stores empty of shoppers. While a boycott was only moderately successful, with many businesses on Dryades choosing to close rather than hire African Americans, it helped to build and organize a larger movement.

A chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) was formed by Rudy Lombard, Oretha Castle Haley, Jerome Smith, and Hugh Murray, a white student from Tulane. On Sept 9th 1960, nine students from CORE (both white and black) decided to “Sit-in” at the Woolworth’s lunch counter at 1031 Canal street. The idea was they would occupy seats at the busy lunch counter until they were served. Eventually the participants were arrested and charged with criminal mischief. Though “Sit-ins” were being used as a tactic nationally, it was the first to occur in the City of New Orleans.

Three days later, Mayor “Chep” Morrison came out against the “Sit-in” saying “the effect of such demonstrations [was] not in the public interest of [the] community” and that the “economic welfare of this city requires that such demonstrations cease and henceforth…be prohibited by the police department.” This in effect banned further sit-ins. Despite this, about a week later on Sept 17th 1960, Rudy Lombard, Cecil Carter Jr., Oretha Castle Haley (Civil Rights pioneer famous for Freedom Rides, who in 1986 was commemorated for her work by having 8 blocks of Dryades St. renamed Oretha Castle Haley Blvd.) and Lanny Goldfinch, who was white, walked into the McCrory’s Five-and-Dime at 1005 Canal Street, located nearby the Woolworth’s, and sat down at the lunch counter. In response to backlash from the city’s white populace for participating in the “sit-in”, Lanny gave the most honest retort, “I just wanted to have coffee with my friends.” This time there wasn’t a media presence, but this particular case did make it to the Supreme Court in 1963 as Lombard v. Louisiana and was thrown out. The City of New Orleans did not have any laws which explicitly segregated lunch counters, which led to the court finding that the actions of the Mayor set a tone allowing for segregation. “These convictions, commanded as they were by the voice of the state directing segregating service at the restaurant, cannot stand,” Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote in his 1963 decision. Even though it would take years for New Orleans store owners to accept desegregation, the actions of the members of C.O.R.E pushed the Civil Rights movement forward.

Years later the Woolworths was abandoned and fell into extreme disrepair after Hurricane Katrina. Plans were devised in 2010 to clear the site to make way for condos and unfortunately would make no effort for preservation or giving mention to the defining history of the location. The site has never commemorated the first lunch counter “sit-in” in New Orleans history and is devoid of even a plaque. In Greensboro, NC, the site of the first lunch counter “sit-in” in the nation, there is now a museum (link) that offers insight into the important role these demonstrations played in United States history.

Controversy was sparked in 2013 when Praveen Kailas the principal manager of Kailas Companies, who would be leading the new construction of 1031-1041 Canal, was found guilty of defrauding a Katrina recovery program. Despite the controversy the City Council gave the green light, 5-2, to approve the construction of a 190 foot, 70 million dollar Hotel and Condo despite the fact that a 190 foot structure is 3 times the size of the zoning limits. In 2014, amidst little protest, the Woolworth’s building was demolished to make way for the planned Hotel and Condos. Construction of the new building started after Kailas Companies cut a deal with Hard Rock Hotels in February of 2018.

This leads us up to today where at 1031-1041 Canal, currently there is a collapsed building which took the lives of three workers. While a Hard Rock Hotel may on the surface seem like a great addition to the revitalization of Canal Street, we need to recognize the histories that paved the way for the building of a more just world. Sadly, now a memorial should be erected at this site as well, which tells a new story of inequality; a story where for the sake of cutting costs and through shady dealings, workers are put in danger and their families have to experience the loss of loved ones, all while the investment firms and CEOs keep widening the gap of disparity. Just as Woolworth’s was not home to the only “sit-in”, neither is it the only site of negligence at the expense of human life. It still seems so recent that eleven workers lost their lives on BP’s Deepwater Horizon oil platform due to corporate negligence and we watched as the Gulf was polluted and our friends and families poisoned for generations to come.

Let us look to those who have risked their lives for a better world as well as to those who have unfortunately lost their lives so that we know what we should still be fighting for.

Love and thoughts to the families and friends of Anthony Lloyd Magrette, Jose Ponce Arreola, and Quinnyon Wimberly.

Great article in Anti-Gravity. I am so very glad I found it and your website, finally someone who speakes truth to reality about issues in this city that everyone should be concerned about. Thanks!